My partner recently injured his hand on a faulty ladder. This took off an area of skin over a proximal finger joint resulting in a dramatic amount of bleeding and an inability to use the finger. Over the days and weeks since we have watched the healing process with fascination, noticing the stages of recovery of both form and function. Normal wound healing has four recognised stages: haemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodelling. For a wound to heal successfully, the four phases must occur in the right sequence and time frame. Many factors can interfere with this process, risking impaired wound healing.

As we watched the re-epitheliation and remodelling of his physical wound it made me think about the unseen wounds many of us have suffered since the start of the pandemic, and the impaired wound healing we have been experiencing. So many people have been harmed not only by the virus itself but also by the lockdowns and the lack of a social safety net, eroded for decades by austerity. I see wounded people often in my work. They are incredibly adaptive and resilient but the body keeps the score, and many chronic diseases and distressing physical symptoms have their roots in emotional and social distress. I cannot speak for these people but I see them. I see their suffering and their strength.

Neither can I speak for all NHS staff, but is is well recognised that the pandemic traumatised healthcare workers. We experienced moral injury long before COVID-19, when we did not have the resources to provide the quality of care we wished to, were let down by a decimated social care system, or were forced to turn people in need away due to factors such as their immigration status. The pandemic brought us challenges that were all too familiar, but, more than that, it highlighted the pervasiveness, severity and proximity of this harm.

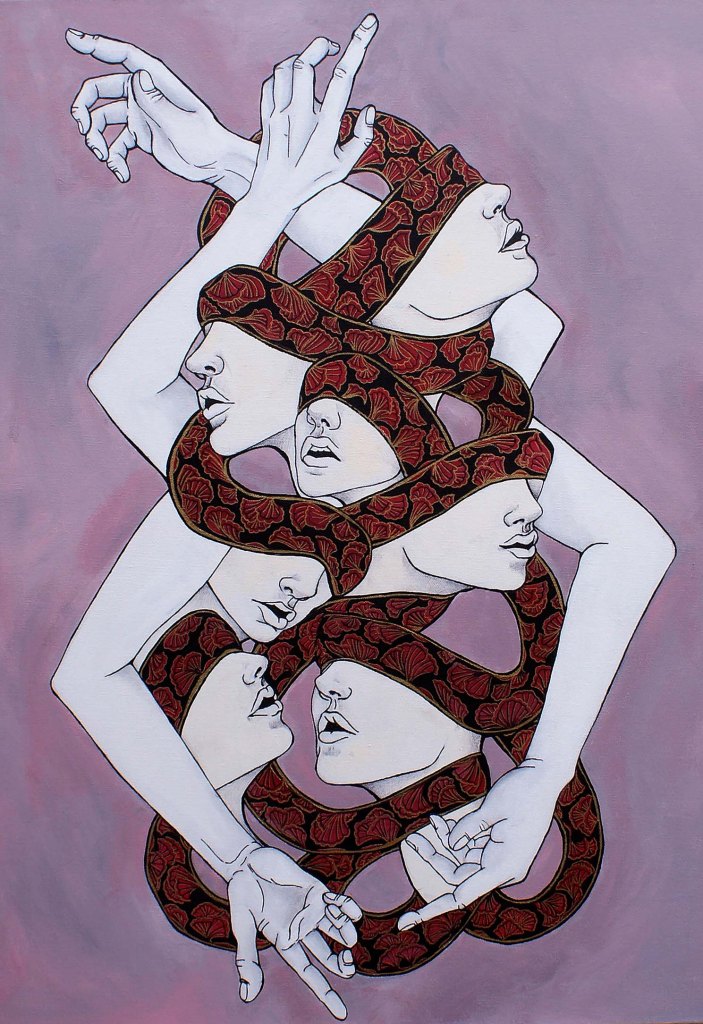

36” x 24” Acrylic paint on canvas, 2017. Cheyanne Silver.

From: www.luc.edu/features/stories/artsandculture/burnoutart/